Phosphorus

Phosphorus has been an issue in Lake Simcoe for many decades. In fact, we began work on addressing phosphorus inputs into the Lake as far back as the 1980’s when we led the formation of the Lake Simcoe Environmental Management Strategy (LSEMS). Since the 1990s, phosphorus loads have been reduced, on average, by more than 25 metric tons each year through source controls and policy.

More needs to be done and more is being done. In 2009, the Province passed the Lake Simcoe Protection Plan (LSPP), and we have been working collaboratively to implement additional policies and practices to reduce phosphorus through the LSPP.

Phosphorus comes from many sources, but one of the most significant sources is stormwater, which picks up phosphorus as it travels across paved and hardened surfaces, especially in densely populated areas.

What's the Problem?

Phosphorus is a naturally occurring element essential for all life. It’s found in plants and animals (and humans) and even DNA; the building blocks of all life. In water bodies such as lakes, a certain amount is necessary, but over time too much phosphorus can cause serious issues including excessive weeds, toxic algae and depleted oxygen levels in our rivers, streams and ultimately, Lake Simcoe.

Because it’s a naturally occurring element, one source of phosphorus entering the lake is from the weathering of rocks and minerals. And because all life consumes phosphorus, a certain amount is excreted in our waste or released from tissues during plant decomposition.

Phosphorus is also a very useful element and can be found in many of the products we use, for example in common every day products like cola, fertilizers, toothpaste, shampoo, matches and flares. It’s also used in pesticides, pyrotechnics, and the production of steel, to name a few industrial uses.

The Phosphorus Lifecycle

The phosphorus in the lake isn’t just in the water. It’s also in the plants, the animals and the sediments. All of these sources interact, share, store and even lock away phosphorus in what we call the “phosphorus lifecycle”.

Phosphorus in the Water

Phosphorus that enters the lake is used by organisms, settles out into the sediments or can remain dissolved in the waters of the lake.

Phosphorus Concentrations

Phosphorus concentration is the amount of phosphorus contained in a volume of water (think of how strong or weak you have a cup of tea or coffee). The current (2018-2021) spring, phosphorus concentrations in Lake Simcoe are 7.1 micrograms per litre, which meets the Ontario water quality objective of 10 micrograms per litre.

This current concentration has been reduced from the 1970-80s when the concentration was 15-30 micrograms per litre. Due to the nature of the lake, and land use in the subwatersheds, some areas (such as Cook‘s Bay, the Holland River, and Barrie) still have higher phosphorus concentrations than other areas.

The decrease in phosphorus concentrations has been achieved through lake management strategies (such as the Lake Simcoe Protection Plan) but other factors can prevent phosphorus from entering the deep water, including water movement due to filtering by invasive mussels and a buffer zone of aquatic plants.

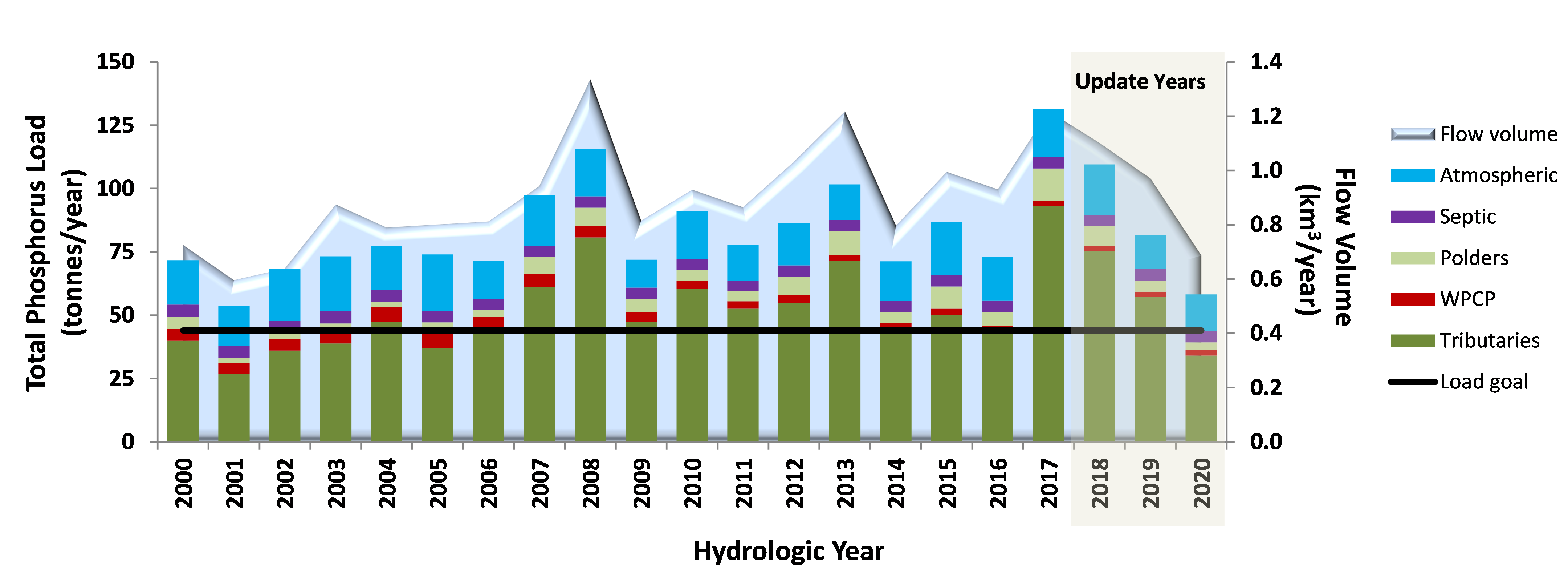

Phosphorus Loads

We don’t just measure phosphorus in the lake (concentrations), we also measure the amount of phosphorus entering the lake: phosphorus loading. A phosphorus load is made up of the concentration of phosphorus in the water and how much water is entering the lake. Keeping with our cup of tea example, a load would be not just how strong your tea is, but how many cups of tea you drink.

The phosphorus loads we report for Lake Simcoe are a measurement of the amount of phosphorus entering the lake from all sources on an annual basis.

Since 2000, the average phosphorus load has been about 83 tonnes per year. Although this is above the Lake Simcoe Protection Plan (LSPP) goal of 44 tonnes, it has declined since the 1980-90s when the average was well over 100 tonnes per year.

As you can see on the graph, there are years of higher phosphorus loads and years of lower phosphorus loads. This variation is being driven mostly by changes in tributary (or river) flow rate (or how much water is entering Lake Simcoe) which, in turn, is driven by yearly differences in precipitation.

The years with highest phosphorus loading on the graph (2008 and 2017) also had the highest tributary flows. Both 2008 amd 2017 were very wet years with higher than average precipitation, a mild winter with several snow melt events, and rain during the winter months that fell on frozen ground and ran directly into rivers. All of these factors create perfect conditions for high runoff, high tributary flow, and high phosphorus loading.

Conversely the most recent year 2020 has one of the lowest loads in the last two decades at 58 tonnes. This is largely due to a dryer than normal year with 10 of the 12 months receiving less precipitation than the long-term average for that month.

One of the major threats to the LSPP, and our efforts to reduce phosphorus loading in Lake Simcoe, is climate change. With warmer winters, we are receiving more rain. So even though we have reduced the phosphorus concentration in the water, more tributary flow means less change in the phosphorus loading.

To circle back to our cups of tea example, even though we are drinking weaker tea, we are drinking more cups and getting the same amount of caffeine!

Phosphorus in the Sediment

Phosphorus is also found in the sediments in the lake. Although plants predominately get their phosphorus from the sediment, not all sediment phosphorus is accessible to plants. As a result of decreasing light penetration, plants are generally not found in water any deeper than 10 metres in Lake Simcoe and therefore sediment at depths greater than 10 metres is considered a phosphorus “sink”.

Phosphorus deposits in the sediment are not evenly distributed throughout the lake. In a lake-wide survey, our researchers recorded the locations of high and low concentrations of sediment. In Cook’s Bay, for instance, there is a very low concentration of sediment phosphorus because it is consumed by the large amounts of aquatic plants. In Kempenfelt Bay and near Beaverton, sediment phosphorus is much higher because there are fewer plants to consume the phosphorus.

Phosphorus in the Plants

Two of the main users of phosphorus are plants and algae. In Lake Simcoe, quagga mussels have filtered out most of the algae which has resulted in higher water clarity, which allows the sunlight to penetrate deeper into the water, encouraging abundant plant growth.

Aquatic plants get up to 97% of their phosphorus from lake sediments. When they die, some of the phosphorus in their tissues is released back into the water, while some remains bound in the plant tissue that will join the sediment. Where these sediments are at a water depth of less than 10 metres deep, the plant tissue phosphorus may be used to fuel plant growth in subsequent years. If the plant material is transported to waters deeper than 10 metres, the phosphorus will become essentially locked away in the sediments.

Positive Changes are Happening

The cycle of phosphorus tells us that there are significant reservoirs of phosphorus in Lake Simcoe and that these reservoirs have been caused by many years of excessive loads. While the lake has many natural processes for absorbing excess phosphorus, when these processes get overwhelmed, the result can be excessive plant growth or algal blooms; indicating a system out of balance.

It has taken many decades for Lake Simcoe to accumulate this much phosphorus and it will take many more to return it to an ecologically sustainable state.

This means that the efforts we are making today may not show immediate results, but positive change is happening. We are now seeing improvements in dissolved oxygen, decreasing phosphorus concentrations and the return of some environmentally sensitive species in the watershed.

What We're Doing

Continued monitoring – We continue to monitor the phosphorus sources throughout our watershed. Monitoring helps better understand how wet and dry years impact our management plans and how we can adapt to new challenges.

Phosphorus offsetting policy – This is a first-of-its-kind policy in Canada and was developed specifically to control phosphorus from new development. The original Phosphorus Offsetting Policy came into effect on January 1, 2018.

Our new Phosphorus Offsetting Policy, approved by the Board of Directors on May 26, 2023, requires that all new development must control post-development phosphorus loadings leaving their property to pre-development levels. This is referred to as a “post to pre” target, which supports the Lake Simcoe Protection Plan’s objectives.

If the pre-development phosphorus loading can’t be met on the site, then developers must pay a fee so that projects to “offset” the phosphorus can be completed elsewhere in the subwatershed. Fees collected for offsets are at a 2.5:1 ratio, meaning, for every 1 kg. of phosphorus that can’t be controlled, the property developer must pay for 2.5 kgs. to be controlled elsewhere. Over time, the restoration projects that are implemented with offset fees, will allow a greater reduction of phosphorus overall.

Some of the types of restoration projects to reduce phosphorus can include engineered wetlands and stormwater pond retrofits.

What You Can Do

You can help reduce phosphorus in stormwater run-off by:

- All fertilizers have 3 numbers on them. The middle number represents phosphorus, so look for a fertilizer where the middle number is “0”.

- Purchasing phosphate free soaps and detergents.

- When using water outside, direct the excess to the lawn or garden and not through the stormwater system. Capture rain water in cisterns or rain barrels to water plants and lawn during drier periods.

- Wash your car at the car wash, where the water will be properly treated. If you must do it yourself, wash your car on the lawn, so that the water soaks into the ground.

- Use native plants in your lawn and garden. They’ve adapted to survive in our climate and therefore don’t have the same need for watering or fertilizer. If you fertilize, look for phosphate free fertilizer.

- Make a donation to the Lake Simcoe Conservation Foundation . Their work supports many Conservation Authority projects for a cleaner and healthier Lake Simcoe watershed.

Interesting fact!

Interesting fact!

Target phosphorus concentrations for lake waters are 10 micrograms per litre.

So you might ask what a microgram per litre is. That is one drop in an Olympic size swimming pool.

That means that our phosphorus target is 10 drops in the swimming pool. Right now we are at 7.5 drops. In the 1980s we had 20-30 drops in the pool!

![]() Where the 44 tonnes comes from

Where the 44 tonnes comes from

The basis of the Lake Simcoe Protection Plan’s target of 44 tonnes per year phosphorus entering Lake Simcoe comes from the ideal dissolved oxygen content in the lake to support a lake wide cold water fishery.

To support a self-sustaining cold water fishery, research says we need a dissolved oxygen content in the lake of 7 milligrams per litre. In order to achieve this 7 milligrams per litre, we need to bring down phosphorus loads in the Lake to 44 tonnes per year.

Report on Phosphorus Loads to Lake Simcoe

Purpose

The Report on Phosphorus Loads to Lake Simcoe 2018-2020 has been prepared by Lake Simcoe Region Conservation Authority (LSRCA).

Phosphorus was identified as a problem for the health of the lake in the 1970s. We have been monitoring it to help us understand its sources and impacts. The purpose of this report is to share with our watershed communities the most current data about the amount of phosphorus entering the lake.

Lake Simcoe Protection Act (2008) & Lake Simcoe Protection Plan (2009)

In 2008, the Province of Ontario implemented the Lake Simcoe Protection Act, which provides the legislative framework for protecting Lake Simcoe and its surrounding watershed. Following the Act was the development of the Lake Simcoe Protection Plan in 2009.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is Phosphorus?

Phosphorus is a naturally occurring nutrient in our environment and is also commonly found in commercial fertilizers and other household products. While Phosphorus is a valuable nutrient that helps plants to grow, such as our lawns and gardens, when there is an excessive amount of phosphorus, it can have a negative impact on our watershed environment, including the quality of water in Lake Simcoe and its river system.

2. Why measure the amount of phosphorus entering the Lake?

In order to improve the health of Lake Simcoe we must know how much phosphorus is entering it and what the primary sources are. When we have this information we have indicators over time to gauge how and if our collective protection and restoration efforts are positively impacting the lake and where to focus efforts to reduce phosphorus.

3. Why do we need to address phosphorus?

Excessive phosphorus has been the most significant cause of water quality impairment in Lake Simcoe and its rivers, or tributaries. It leads to excessive aquatic plant and algal growth in the lake.

When algae decay in the deeper areas of the lake, they create an oxygen shortage that affects coldwater fish such as lake trout and lake whitefish, which need sufficient levels of oxygen to survive and reproduce. Although there is more oxygen available in the deep cold parts of the Lake now than there was 30 years ago, we still need to work on raising the oxygen levels so the fish community can sustain itself. This means reducing the amount of phosphorus that goes into the lake.

High levels of phosphorus also contribute to nuisance aquatic plants.

4. Is phosphorus reduction the only indicator being used to measure the health of Lake Simcoe and its watershed?

No. Phosphorus reduction is only one of several indicators identified in the Lake Simcoe Protection Plan for measuring the lake’s health. The Lake Simcoe Protection Plan identifies and directs a multitude of actions required to restore the overall health of the Lake, including:

- restoring the health of the coldwater fishery and other aquatic life

- improving water quality, including reducing the amount of phosphorus going into the lake

- maintaining water quantity

- protecting and rehabilitating important natural areas such as shorelines, and

- addressing impacts of invasive species, climate change and recreational activities.

5. How often is the phosphorus report issued?

Reporting on the phosphorus loads to Lake Simcoe is typically done every three hydrological years. It takes approximately two years to collect, review and analyze the data provided by a number of partner organizations. Detailed quality assurance checks are conducted on the data and the loading calculations to ensure that the phosphorus loading results are accurate.

6. When was the last Phosphorus Loads Report issued?

The most recent load calculations were posted at the beginning of 2020 in the form of an update on the LSRCA website. This update presented findings on how much phosphorus entered the lake in the 2015, 2016 and 2017 hydrologic years. See Phosphorus Loads Update, 2018 –2020 to read the entire report.

What are the results from the current report on phosphorus loads to Lake Simcoe?

This update presents findings on how much phosphorus entered Lake Simcoe from various sources in 2015, 2016, and 2017 hydrologic years.

The overall results show that the first two years of the reporting period had average phosphorus load amounts entering the lake, such that 2015 had 87 tonnes and 2016 had 73 tonnes. But 2017 was a high load year, contributing 131 tonnes of phosphorus, which was attributed to a wetter than normal year. In this year, the watershed experienced two large runoff events that alone accounted for 20% of the total annual load.

7. Why are phosphorus loads higher during a wet year?

Phosphorus loads fluctuate over time due to constantly changing factors such as weather.

Phosphorus load levels in tributaries, such as a river or stream, are a combination of phosphorus concentration – that is, the amount of phosphorus in each litre of water – and water flow, so increased water flow will result in an increased phosphorus load level. For example, if the phosphorus concentration level is low in a tributary, such as a river or stream, but the water flow is increased due to heavier than normal precipitation, the phosphorus load could also increase.

Phosphorus is transported into rivers, streams and the lake during rainfall and snowmelt events. During extremely wet years more phosphorus can be transported into the tributaries and Lake Simcoe increasing the total phosphorus load. Since we cannot control the weather, we try to reduce the sources of available phosphorus and stop it from being washed into tributaries and the lake.

8. How has phosphorus loading changed since the early 1990s?

The average phosphorus load to Lake Simcoe is lower now than it was during the early 1990s when it was consistently well over 100 tonnes. The Lake’s water quality has improved as well, with more oxygen available to fish in the deep waters of the lake as well as lower phosphorus concentrations in the spring.

9. What is guiding our work in Phosphorus Management?

Under the Lake Simcoe Protection Plan, the province has set a phosphorus loading goal of 44 tonnes per year. It represents an ecological target to create optimal conditions for the cold water fishery in Lake Simcoe.

In June of 2010, as part of the provincial Lake Simcoe Protection Plan, the Ministry of the Environment released the Lake Simcoe Phosphorus Reduction Strategy. This strategy identifies specific reduction goals and potential reduction opportunities for each major source or sector of phosphorus within the watershed.

10. How will reductions in phosphorus be achieved?

Ontario’s Phosphorus Reduction Strategy for the Lake Simcoe watershed is based on shared responsibility to continually reduce phosphorus loads over time. These actions are designed to achieve proportional reductions from each major contributing source.

The strategy uses an adaptive management approach, which allows us to update or revise it as new science and technology that could help us meet the targets becomes available. The strategy will be reassessed every five years.

We have a history of success in working closely with watershed partners. We will review and update the Phosphorus Reduction Strategy, as necessary, to ensure its success.

LSRCA undertakes numerous activities and projects, in collaboration with our many municipal, community and other government partners, to reduce the amount of phosphorus being washed into the lake, including:

- innovative technologies such as engineered wetlands

- state-of-the-art stormwater retrofits

- private landowner stewardship projects to reduce and prevent soil erosion and restore natural buffers along streambanks

- community tree planting events and workshops

- working with the agriculture industry to implement best management practices for a multitude of farming activities

- classroom and outdoor education programs for youth

- public outreach at fairs, festivals and through community group activities

To learn more about what we do, check out the about us section of our website.

11. What can I do to help reduce phosphorus from entering the lake?

There are many ways that we can all contribute to decreasing phosphorus input to Lake Simcoe, some are as simple as switching to phosphate-free fertilizer, eliminating pesticide use, leaving a natural buffer along rivers, streams and creeks and planting rain gardens.

Each and every facet of our modern-day lives impacts the health of our Lake and the watershed as a whole. We have a shared responsibility to work together, continually, to reduce our impact on these essential natural resources.

The Public Report on Phosphorus Loads 2015-2017 contains information on how to connect to provincial, municipal and Lake Simcoe Region Conservation Authority resources and programs.

You can also visit the Ministry of the Environment’s website to find out What You Can Do To Help – My Actions, Our Lake Simcoe or continue to explore our LSRCA website.

Ministry of the Environment (MOE)

The MOE is responsible for protecting clean and safe air, land and water to ensure healthy communities, ecological protection and sustainable development for the people of Ontario.

Using stringent regulations, targeted enforcement and a variety of innovative programs and initiatives, the ministry continues to address environmental issues that have local, regional and/or global effects.

Lake Simcoe Region Conservation Authority (LSRCA)

Established in 1951, LSRCA provides leadership in the protection and restoration of the environmental health and quality of Lake Simcoe and its watershed. Working with our community, municipal and other government partners, we deliver important environmental programs and services.

Our role as co-authors of this report is to provide scientific data collected through our lake monitoring program and the analysis of that data.

![]() Who to Contact

Who to Contact

Integrated Watershed Management

✆ 905-895-1281

✆ 1-800-465-0437 Toll free