Lake Simcoe Science

Low Impact Development (LID)

A Recipe for Urban Sustainability

In previous issues of our Science newsletter, we’ve explored the problems associated with urban stormwater run-off, a major contributor of pollutants entering into our rivers and ultimately into Lake Simcoe itself.

Urban stormwater run-off is responsible for around 20 per cent of the phosphorus entering the lake. Given this large amount, staff at LSRCA are engaged in reduction efforts focused on stormwater because we know the outcomes will have a big impact.

A Diet Low In Stormwater is Good for Your River

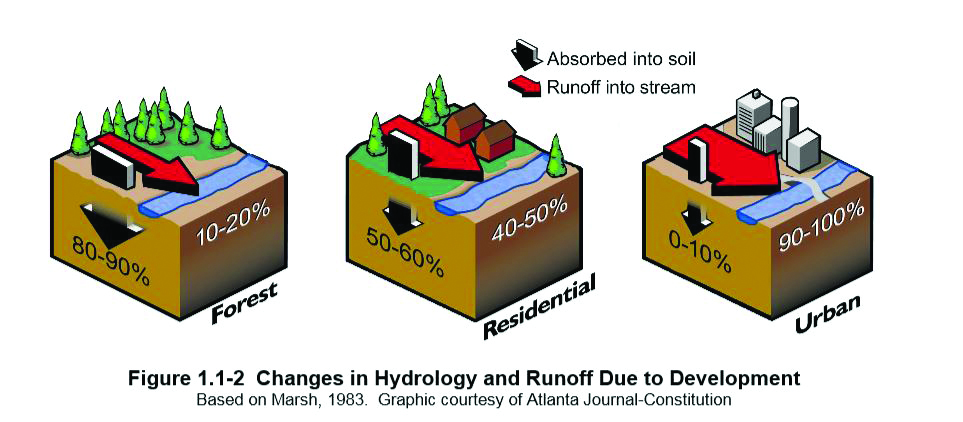

When land is developed, the natural water cycle is changed. Clearing the land removes the vegetation that intercepts and allows precipitation (rain/snow) to seep into the ground. Paving makes surfaces hard and actually increases run-off. The result? Lots of water coming down in the form of rain and snow, but no way to enter the ground. Instead, it travels along the hardened surfaces, picking up contaminants along the way, eventually draining into our rivers and streams.

Traditional stormwater ponds were designed to make up for this change to the natural water cycle by holding the water in reservoirs, quickly moving it away from homes, and slowly releasing it to the rivers and streams.

In this way, it did work. However, over time, the shortcomings of traditional stormwater ponds became apparent:

- While a traditional pond can slow the speed of stormwater entering our rivers, it does not address the additional volume that is generated. It’s this increased volume to the rivers that causes stream bank erosion, degraded habitat and, when combined with many other such ponds, downstream flooding.

- Along with this extra volume of water comes additional pollutants, the most important of which in the Lake Simcoe watershed is an increase in phosphorus. Did You Know… In 2013 LSRCA issued 14 bulletins advising of potential unsafe conditions due to flooding.

- Stormwater pond maintenance costs and requirements were underestimated. A 2010 LSRCA study found that ponds are filling up with sediments faster than expected. Removing the sediment is expensive because, often times, the pollutants it has accumulated leave it as a contaminated waste, making disposal costly. In addition, stormwater ponds that are full of sediments are not operating at peak efficiency.

- During hot dry spells, the dissolved oxygen in pond waters can be consumed by biologic processes. This state of hypoxia (low oxygen) or anoxia (no oxygen) can promote the re-release of phosphorus bound to sediment. This was documented in many ponds in the 2010 LSRCA study and means that, at certain times of the year, these ponds that we are relying on to contain phosphorus may actually release additional phosphorus.

- Stormwater is often warmer than its receiving waters. All this warmer water entering our streams and rivers can be harmful to some forms of aquatic life, which prefer cooler temperatures.

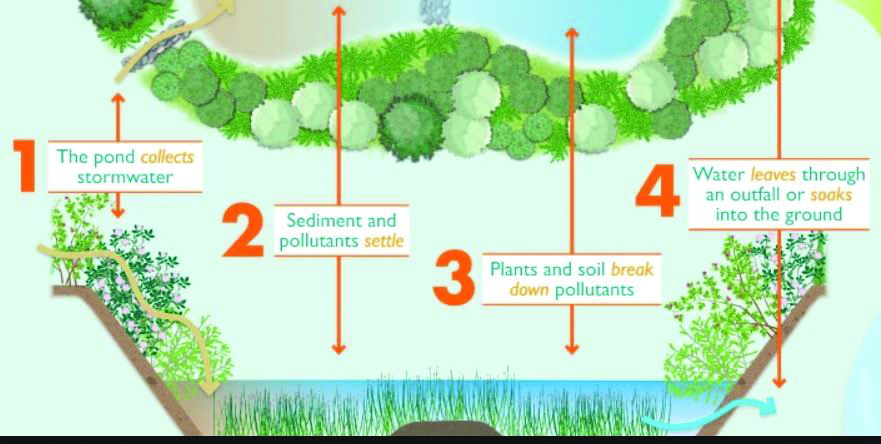

How Stormwater Ponds are “Supposed” to Work

A storm water pond is an artificial pond designed to collect and retain urban stormwater, releasing it slowly to protect f looding downstream and reducing sediment. However, over time, the shortcomings of traditional stormwater ponds became apparent. Graphic by the Watershed Company.

A New Cuisine for Streams: Low Impact Development

As communities continue to grow and expand, we know doing more of the same thing isn’t going to work. LSRCA staff and researchers have been exploring alternative strategies to manage stormwater run-off in a more sustainable manner. They’ve come up with a menu of choices that improve upon the traditional stormwater pond approach. Low Impact Development is seen as a possible solution. By no means a new concept, Low Impact Development has not gained significant traction in Canada yet. LSRCA hopes to change this.

The Stormwater “Menu”

LSRCA researchers have been collaborating with organizations that have successfully implemented Low Impact Development projects in the US. Our goal is to take the lessons learned from their experiences and apply them to the urban landscape here.

The strength of Low Impact Development is that it tries to mimic the natural hydrologic cycle. In other words, help to move water into the ground the same way it did before houses or parking lots were built there. As discussed above, the key function that development interferes with is the ability of stormwater to soak into the ground. Therefore, Low Impact Development will rely heavily on methods that address this extra volume of water through infiltration, storage, reuse and finally, filtration.

Low Impact Development approaches use a “treatment train approach”. This means a number of measures will be used throughout the community to manage runoff and keep it as close to its source as possible. This starts on individual properties managing their own run-off as much as possible, then using the next treatment technology in the train to address excess run-off until the required amount has been addressed.

Changes in Hydrology and Run-off Due to Development

The natural water cycle is changed when land is developed. The amount of infiltration vs runoff in various landscapes can be dramatic. Graphic: Atlanta Journal Constitution.

We need to manage growth

More than 12,235 hectares (122 km 2) of new urban area is anticipated to be built in the Lake Simcoe watershed by 2031. Traditional stormwater management is not a viable option if we are to try and reduce the pollution entering the lake.

Low Impact Development Benefits

- Mimics the natural product.

- Treats water at the source

- Allows water to infiltrate because it tries to more closely directly into the ground

- Maintains groundwater community that has more green space and native landscaping.

- Assists with flood control

- It can even fit into older have a role in providing flood communities that do not have the space for conventional stormwater controls

- Helps communities build resiliency to climate change

- Cheaper in the long run than conventional stormwater ponds

- It looks nicer (and can increase property values)

What Does Low Impact Look Like?

Low Impact Development begins in the planning stages, well before any shovels hit the ground. It’s incorporated into the design of the community, taking advantage of natural landscape features, minimizing impervious surfaces like pavement, and treating stormwater as a resource rather than a waste product. For these reasons, it could best be described as more holistic in its approach to stormwater management, because it tries to more closely mimic the natural water cycle. The result is a more resilient community that has more green space and native landscaping.

While stormwater ponds will still have a role in providing flood protection, these won’t need to be large stormwater ponds, because most of the run-off is being managed locally on individual properties.

Low Impact Development Strategies

Four low impact development strategies – green rooftops (top left), rain gardens (top right), rainwater harvesting (bottom left), and permeable pavement (bottom right).

Challenges to Low Impact Development

Because Low Impact Development has been tried in other jurisdictions, we have the advantage of learning from others’ experiences. LSRCA is working with these partners to develop strategies to overcome the challenges associated with Low Impact Development in Ontario. Some challenges, such as how to deal with cold weather and frozen soils, are easier to overcome. Others though, like changing people’s way of thinking and doing things, take much more time.

Making This Work

The reality is that we have no choice if we hope to achieve the health targets set for Lake Simcoe. The current stormwater approach is not feasible in the long run given development will continue. We have to make changes and we have to do it now.

To that end, LSRCA is actively engaging with the development industry to drive a market transformation in the way communities are designed and built. So far the response has been extremely positive, and not just because it makes sense to the industry, but because there is a demonstrated demand from the public.

The first such development in the LSRCA watershed is the Mosaik Homes community in Newmarket that saw properties near or with Low Impact Development features among the first to sell. More of these communities are on the way and what is now the exception will hopefully soon be the norm for all new development in the watershed.

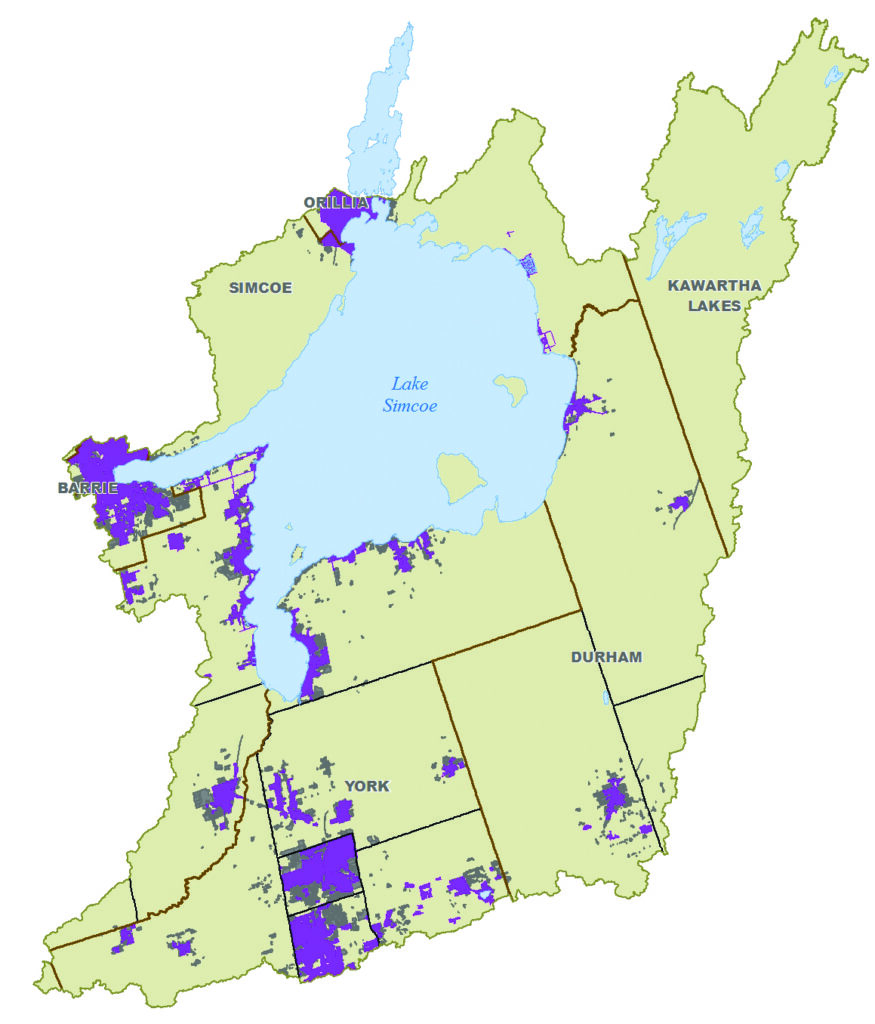

Urban Areas without Stormwater Control

Lake Simcoe has around 200 stormwater management facilities. However, as much as 60 per cent of the urban area of the watershed has no stormwater control at all. These areas would particularly benefit from individual landowner participation in our RainScaping program. These areas are shown in purple in the map below.

Getting Involved with Low Impact Development

If you’re thinking of buying a new home, ask the builder what steps they’re taking to manage stormwater. Take advantage of any extras that they are offering in terms of “green” development. Now’s the time to incorporate it into your property rather than paying to have it added later.

Who to Contact:

Customer Service

Phone: 905-895-1281

Toll Free: 1-800-465-0437

Email: info@LSRCA.on.ca